The Hastert Rule and Congressional Polarization

When parties in Congress refuse to work together, Democrat majorities appear more ideologically liberal and the Republican majorities appear more ideologically conservative than the public at large.

The “Hastert Rule” has received some attention in the press this year, as some House conservatives have demanded that Speaker Kevin McCarthy not bring up any legislation that does not pass this test. The Hastert Rule states that the Speaker will only bring a bill to the floor “if the majority of the majority” supports it.

The Hastert Rule is not a formal rule but a guideline leaders of both parties have followed since the 1980s as part of the shift away from strong committees to party leadership. The rule’s consequences have resulted in a highly polarized Congress that behaves like a parliament with none of the efficiencies.

Some basic information about the House of Representatives is important to understand the Hastert Rule. The House is based on the majoritarian principle – the idea that House Rules are specifically designed to allow a determined majority to achieve its policy objectives. The history of the House of Representatives is one of steadily increased power for the majority at the expense of the minority. Walter Oleszek writes, “The principle of majority rule is embedded in the rules, precedents, and practices of the House.” As a result, the House is structured to enact the will of the majority party, and victories by the minority are supposed to be, by design, extremely rare.

And this is exactly how the authors of the Constitution had designed the system – they believed the House should act on the will of the majority of voters. After all, the House was, at the time, the only body elected directly by the people. In George Washington's words, the Senate would cool the “hot passions of the House.” Keep in mind, however, that when the Constitution was ratified, there were no political parties in the United States. There were indeed regional interests, differences over the size and scope of the federal government, and differing philosophies of governance, but Congress was not a partisan-dominated institution.

Which raises a question - just what constitutes a majority? If by a majority, we mean 218 votes on any amendment or bill voted on by the House, there is the possibility of changing majority coalitions on any number of different issues. Agriculture interests might band together against urban interests. States that do not receive an equitable share of highway dollars relative to the taxes paid by their constituents (donor states) might band against states that receive more funding than their taxpayers paid for. These majorities form naturally along the lines of constituent interests, and a Member could be with a majority on one issue but not another.

If, however, we mean the majority party must pass its own agenda without the participation of the minority, then the definition of a majority means something entirely different. Under this philosophy, Congress begins to behave more like a parliament that votes by party rather than a legislature where members are elected independently. In a parliament, members serve at the pleasure of their party, and if the majority party falls, new elections are called. In a democratic republic, members are elected by individual constituencies, and their primary loyalty, in theory, should be to the interests of their constituents. A Republican from a rural district in the South will not always agree with a Republican representative from an urban manufacturing district in Ohio.

Since the 1970s, when power shifted from Committees to party leadership, the House has operated under what political scientists call conditional party government. This was a term developed by political scientist David W. Rohde, currently at Duke University. Rohde argued that the reforms of the 1970s increased the power of party leadership and created a situation where Members of the majority party believe their political opportunities are enhanced by supporting the position of the party leader. In turn, the party leader will not propose a bill unless a consensus exists within the party.

In effect, Members willingly cede their own independence to their party leaders in exchange for the promise of political help and protection in the next election. The idea is that a party that can successfully enact its agenda will be better able to raise money and get its members reelected. The leaders then use their absolute control of the procedural apparatus of the House to enforce their will on the House floor, and they use the rules to block difficult amendments or resolutions that might make their Members have to take a tough vote.

Former Speaker Dennis Hastert succinctly summed up conditional party government when discussing why he did not allow the Democrats to participate in drafting the 2003 Medicare prescription drug. In stating what is now known as the Hastert Rule, Hastert said such bills would reach the House floor only if "the majority of the majority" supports them. That is the essence of conditional party government. And not coincidentally, the Medicare legislation that passed by a wide bipartisan majority in the Senate passed under a much tighter margin in the House of Representatives.

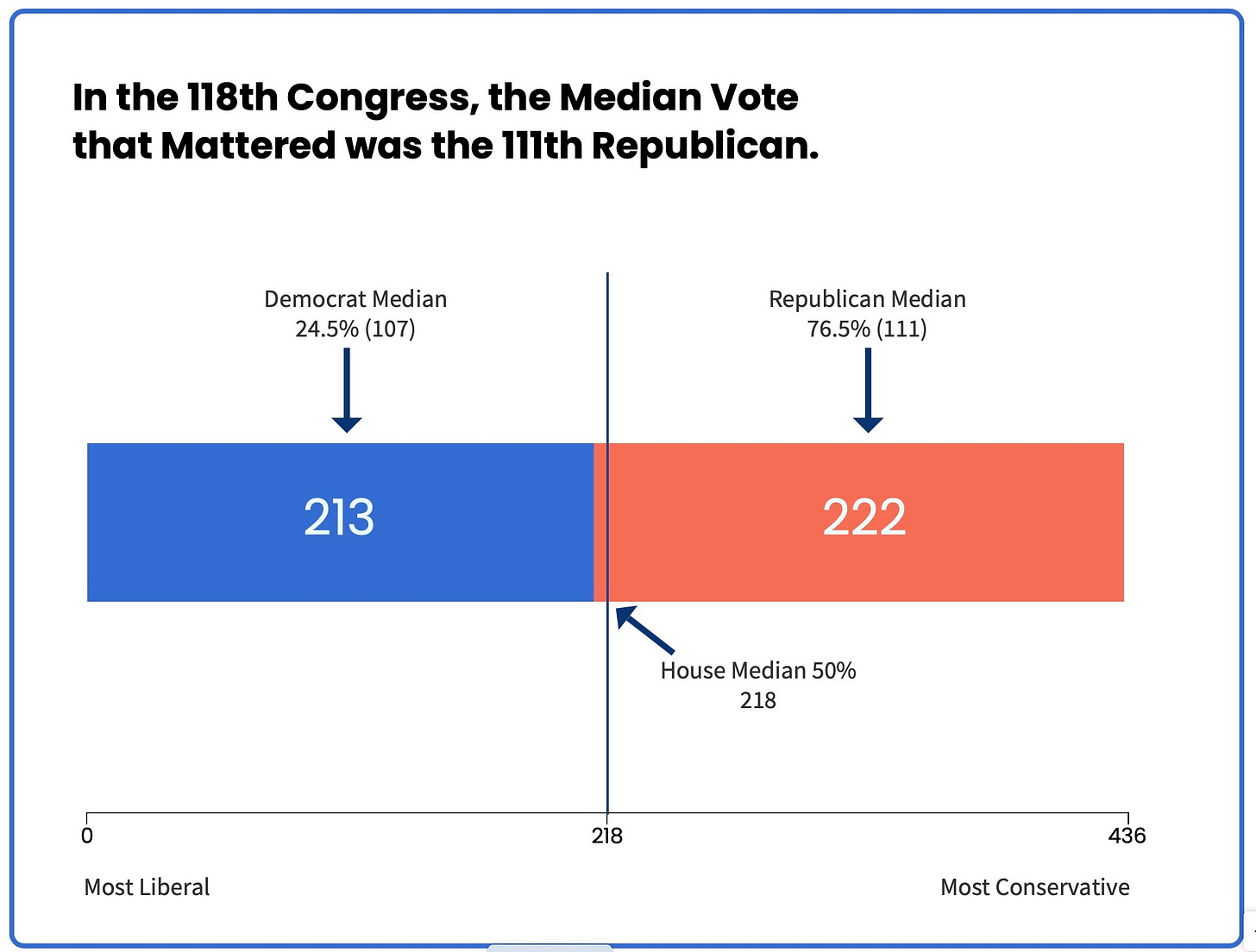

The working majority, therefore, is not 218 votes but rather the median vote in the majority party. Follow me closely here. In the 117th Congress, the Democrats had 222 votes, and the Republicans had 213 votes. Under the theory of conditional party government, the majority of the majority was 112 votes – half of the 222 Democrats.

If you put the House of Representatives on an ideological scale, the most liberal Member’s ideology was represented by 0%, and the most conservative Member was represented by 100%, the 112th vote, or the “majority median vote,” was scored at 25.5%. For perspective, that means 74.5% of the House was more conservative than the majority median vote. As a result, the party leadership's position was significantly more liberal than the midpoint of the entire House.

Following the 2022 elections, Republicans gained a majority of 222 Members. Under conditional party government in the 118th Congress, the majority of the majority would be 112, which would be 74.5% on the ideological scale. That means the 112th most conservative Member would be the median for determining the House's vote. Consequently, the party leadership's position would be significantly more conservative than the midpoint of the House (218).

An observer of the American political system can understand why the Democrat majorities in Congress appear more ideologically liberal than the population at large and the Republican majorities appear more ideologically conservative than the American electorate.

Conditional party leadership is, by its nature, more polarizing. And both parties have adopted it when they are in control. Today it is used by Republicans, but last year it was used by Democrats. By its very nature, the political minority is excluded from the agenda-setting process. As a result, the Speaker cannot count on any votes from the other party. This dramatically reduces options. In the current Congress, to satisfy party members, a bill must be far enough to the right to capture the extreme but not so far to the right that it alienates its more moderate Members.

In fact, under the Hastert Rule, the majority party manipulates the floor procedures of the House to block bipartisan compromises that might challenge the majority position specifically. “The rules of the game are easy enough to manipulate by a majority party to foreclose opportunities to vote on alternatives that would attract bipartisanship,” said Sarah Binder, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

There are some caveats and complications to these strong-arm tactics of the House majority. First of all, it requires a relatively cohesive majority. In other words, leadership still has to pass legislation – and if it is going to steamroll the minority, it has to ensure it can still get 218 members of its own party to support the legislation on the floor. This can empower a small minority of the majority party to be able to blackmail their colleagues with the threat of voting against the majority’s agenda. In the current Congress of 222 Republicans, just five individual Republicans can threaten to vote against legislation and prevent the Speaker from passing the bill. In the past, under such a threat, the Speaker would have moderated the bill sufficiently to gain enough votes from the minority party to pass the legislation – making the final bill even less attractive to the renegades.

For instance, when the Civil Rights Bill passed in 1964, the Democrat Speaker faced massive opposition from southern Democrats in his own party. President Johnson appealed for Republican support, and 80% of the House Republicans rallied to the Democrat president and passed the Civil Rights Act. The final vote had 152 Democrats for and 96 against – well short of a majority, but 138 Republicans for and only 34 against, allowing for a comfortable bipartisan majority of 290-130.

Compare that to a recent key vote, when Speaker Pelosi passed the American Rescue Plan in February 2021 without a single Republican vote. The Civil Rights Act passed with bipartisan majorities in the undisputed consensus of the American public and has never been challenged. The American Rescue Plan faced widespread opposition from the public and in Congress and is cited as the fuel that fired the surge in inflation over the last two years. It will not be a vote Members brag about.

In the recent past, when Congress did not behave in such an extreme partisan manner, a Speaker could go to their more recalcitrant members and say, “I’d love to do a deal with you to get this bill passed. But if I put your amendment in the bill, it won’t pass. So I need you to compromise. If not, I will go to the Democrats and offer them an amendment that moderates the bill just enough to offset your opposition. The bill will be less conservative than the compromise, but we will get most of what we want.”

In that case, the more conservative members would have to settle for less than they wanted to make the final bill as conservative as possible while still passing. Today, the more extreme Members of the Republican Conference do not feel like they have to compromise because no Democrats can be counted on to offset their numbers on any given issue.

Of course, the great irony is that the small band of Republican renegades in today’s Congress only want to follow the Hastert Rule when they agree with the majority of the Conference. They have no difficulty splintering off on votes where they oppose most of their colleagues like they did last week on the Agriculture Appropriation Bill. In the end, this will either be their undoing or the undoing of their Republican colleagues. Either the public will grow tired of an ineffective majority and vote them out of office, or their fellow Republicans will grow tired of being held hostage to the most ideologically extreme of their colleagues and will begin to offer opportunities for more like-minded Democrats to participate in crafting legislation.

That is if there are enough moderate Democrats left to form a working majority coalition with – but that is a post for another day.